Me In Three (Mostly Not Problematic) Books

Today, over at Culture Study, Anne Helen Petersen is asking readers: “What are the three books that are foundational for you and why?” I love this question so much that I’m using it as a prompt for a post. Please feel free to share your own foundational books in the comments.

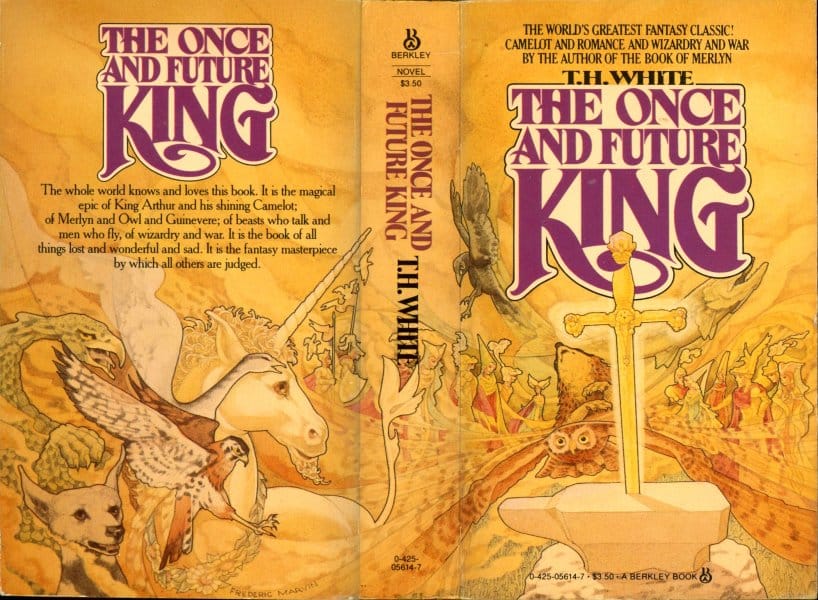

The Once and Future King by T. H. White. I didn’t realize this until right now, but the edition of this book that called out to me from across a tiny bookstore in Akron, Ohio, must of have brand new when I bought it as a 12-year-old. In retrospect, I can see that the cover art that lured me in is very 1982, which is to say pretty 70s but with certain je ne sais quois that is maybe just the unicorn on the back. Anyhow...

I loved this book the first time I read it, and I’ve loved it anew the 30+ times I’ve reread it. The parts of the book I found enchanting are mostly enjoyable as nostalgia now, while the parts that I tended to speed read as a kid break my heart now. But, still, I notice something new—and maybe learn something new—with each reading. It turns out that this is a perfect book for a smarty-pants, myth-obsessed tween and for a smarty-pants, myth-obsessed woman in late middle age.

At the level of craft, The Once and Future King is unassailable. T.H. White created a sort of self-aware, arch-but-earnest postmodernism that is all his own. This is an intensely moral book, and it is completely lacking in irony. I believe that White plays with storytelling conventions because it’s fun and because it’s the only way he could tell the story he needed to tell—a story that I’m convinced flowed fully-formed from his pen.

Worth mentioning: White published the short novels that would become his magnum opus between 1938 and 1940, and his thoughts on fascism are entirely clear. (There’s a section of the book, in which the young Arthur is transformed into an ant, that—to my mind—presages 1984.)

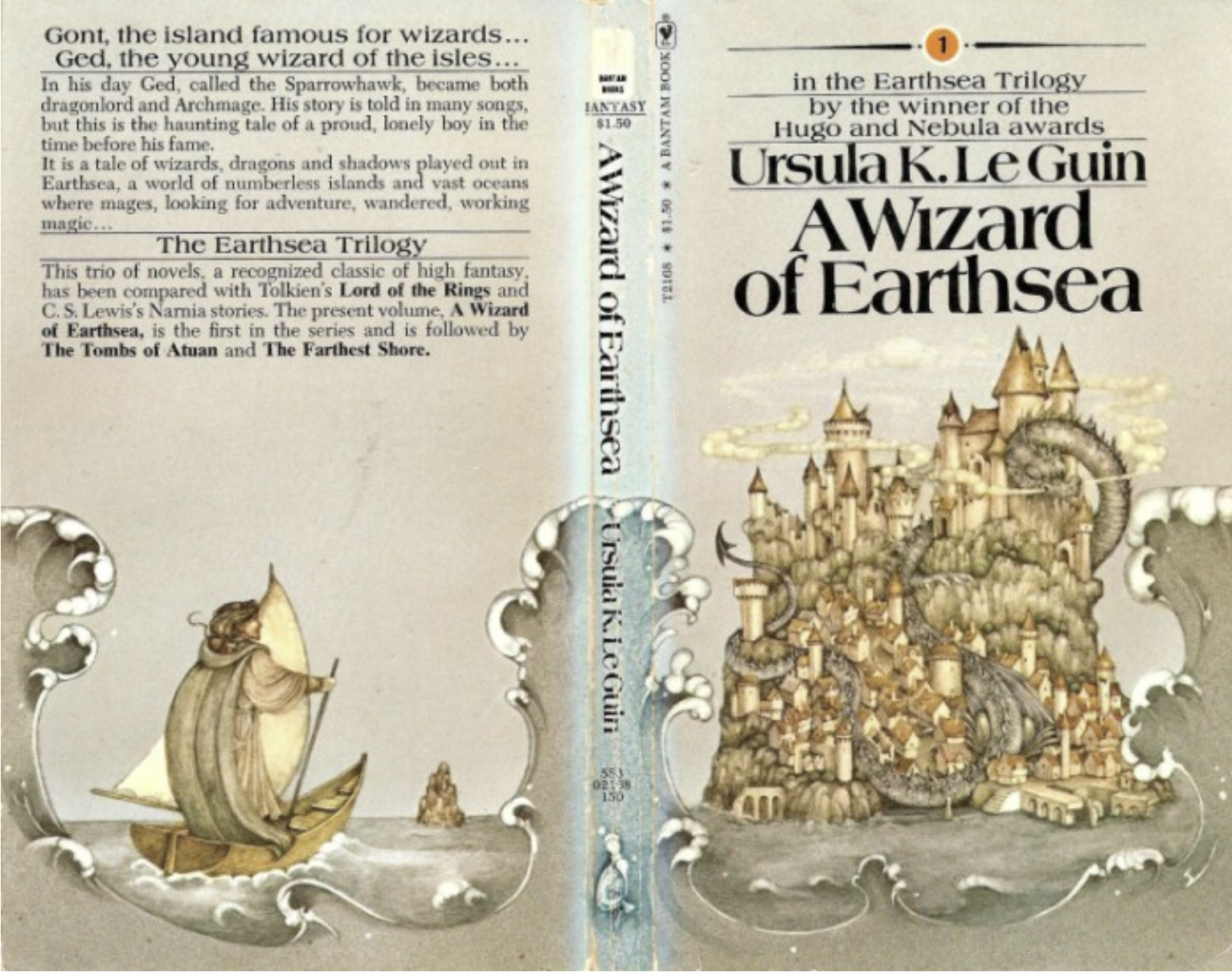

A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin My parents didn’t censor what I read, but occasionally my dad would make me read something. This is one of the books he made me read. I don’t think I took a lot of convincing. I mean, just look at that cover.* Who wouldn’t want to know what was happening here?

I don’t remember how old I was when I read this, but it was early enough that Earthsea is a place that lives in my brain the same way Manhattan does—I’m a visitor, but I know my way around. Le Guin’s philosophy, in many ways I can only recognize in hindsight, became my philosophy, and I was lucky enough to get to talk to her about it once.

In Earthsea, magic has weight—which is not something I can say about another invented world with a school for wizards. Magic has consequences, and making magic costs not just the maker but the whole web of creation of which they are a part. One of the lessons that Ged, the protagonist of A Wizard of Earthsea, learns is that magic should be a last resort, and that we should only transform even the tiniest element of it when we understand that part of the web and its relationship to the whole. An impossible standard to maintain, maybe, but one to strive for, nevertheless.

*A note about Ruth Robbins’ art: You will note—or maybe you won’t—that the figure on the back cover, which is supposed to be Ged, is white. In her text, Le Guin makes it explicit that Ged has copper-brown skin. The first edition of the book may be the only cover that depicts this. (In the interior artwork for The Books of Earthsea: The Complete Illustrated Edition, artist Charles Vess makes Ged brown. Ged only appears as a tiny, indistinct figure on the cover, though.)

The Mists of Avalon by Marion Zimmer Bradley This is another book I remember seeing for the first time. I found it when I was 14 or 15 at the Walden Books in Chapel Hill Mall.*

I assume that many a Gen X witch found her way to feminine spirituality through this retelling of Arthurian legend through the eyes of Arthur’s sister, the priestess Morgaine. This was, for sure, the first book in which I began to see patriarchy as anything other than just the way things are. I’m not saying that I wasn’t raised to believe that I could do whatever I wanted to do and be whatever I wanted to be, and it’s not like I fully awakened to systemic injustice when I read this book. But I think The Mists of Avalon did open my eyes to the reality that we create the systems that define our culture, that these systems are not inevitably. The story of Arthur is always a tragedy and the story of Morgaine is a tragedy, too, but the vision of a world in which women had authority without turning themselves into pretend men had a huge impact on my sense of self and my sense of what was possible.

There are few things I love more than making book recommendations, and I have suggested or given The Mists of Avalon to a lot of girls. I don’t do that anymore, because I don’t want to give girls the burden of Marion Zimmer Bradley’s legacy. I wrote about this for Electric Lit in 2017, so I’ll refer you to that essay rather than offering a synopsis.

*In the essay, I say that I was 13 when I found this book. I was guessing from the pub date. Now, I’m pretty sure that I read it a bit later. Fifteen seems likely. Fourteen seems possible. Probably the only way to know for sure is to ask a scientician to date a drawing of Morgaine that is framed and still on display in the house where I grew up.

Thank you for reading and thank you for following me to Ghost. I’m still figuring out this platform, and I appreciate your patience while I do.

Comments ()