Becoming a Soul-Friend

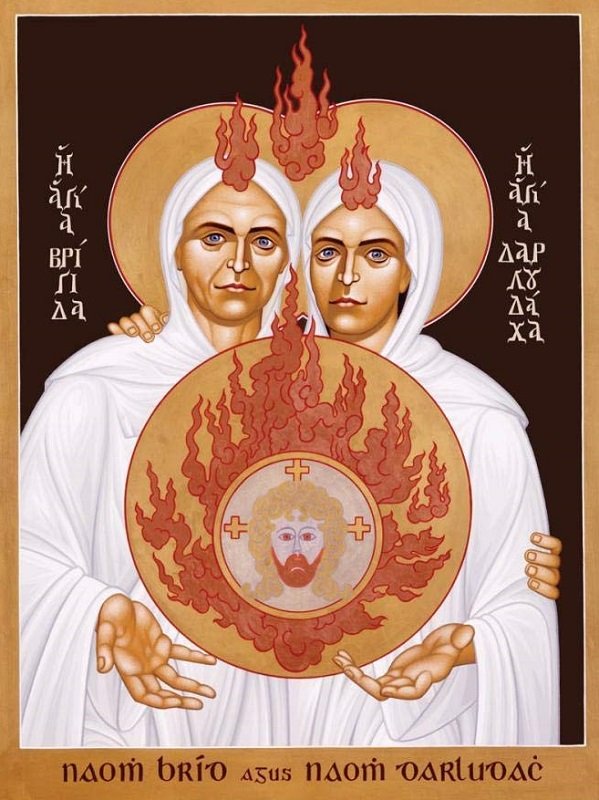

According to legend, St. Brigid of Ireland, Abbess of Kildare, was dying, he close companion Darlughdach said that she wanted to die, too. Brigid insisted that Darlughdach survive her, promising her close companion that she would join Brigid in death in just one year. Darlughdach endured, served as abbess for a year, died just as Brigid had predicted, and became a saint herself. Darlughdach now shares a feast day—February 1—with her more famous friend.

Queer theologians have taken Brigid and Darlughdach into their hearts. Whether or not these women had a sexual relationship is unknowable and, to me, doesn’t matter. They shared a bed, and they also shared a lifelong partnership at least as committed as any heterosexual pairing.1 Whatever the details of their union, I can say with some certainty that Brigid was Darlughdach’s anamchara.

Anamchara means “soul-friend.” Some contemporary people translate the word as “soulmate,” but this is misleading, as we tend to think of soulmates as romantic partners. An anamchara is a beloved friend, a singular friend, but also very specifically a friend who cares about the state of our spirit. This term could, for example, be used to describe someone’s confessor. Understanding this helps us make sense of what St. Brigid means when, according to the Martyrology of Óengus the Culdee, she tells a foster-son who’s anamchara has just died that he must find another one immediately, as “anyone without a soul-friend is like a body without a head.” Cogitosus, Brigid’s first biographer, begins her story by describing her role as a leader within the Church. “Her interest,” he writes, “was to provide in all matters for the orderly direction of souls”—an idea that aligns nicely with her belief in the importance of having an anamchara. I see a soul-friend is someone who loves us enough to want what’s best for us and is wise enough to give us straight talk when we need it.

In an essay about outgrowing the Roman Catholic Church and reconnecting with the native spirituality of her home country, Brigid Murphy—a nun, as it happens—reflects on assuming the role of anamchara and embracing cronedom at the same time:

To be a soul-friend is to work against the dualism that afflicts each one of us in the western world. It is to walk with another in a nonjudgmental way, putting that person in touch with her/his own story, her/his own voice, and encouraging them to trust it. It is to see the living connection between ourselves and all of creation.

Reading Murphy’s words, I think of the older women in my church who have made my son and me feel at home, and who also offer me help when I need it. I think about the Unitarian Universalist commitment to building the beloved community—a place where everyone is welcome, just as they are. And I think about how the interconnectedness of all life is a core tenet of our faith.

Of course, I think of my own dearest friends, as well as the people who I have gotten closer to as the little differences that meant so much to us when we were younger are meaningless now. This is especially true of alumnae from my college. Say what you will about social media, but Facebook made it possible for me to get to meet people for a second time when nobody cares who ate in which dining hall between. I cannot count the number of times I have seen this extraordinary cohort—mostly women, but also a couple of transmen and at least one nonbinary alum—come to each other’s aid. I can’t even begin to quantify what I’ve learned from being a part of this collective.

And I think about being a good ancestor, which is actually something I think about a lot. I think about it as a parent, but also as a public servant and an activist. Lately, I’ve been easing into the idea of stepping away from positions of (patriarchally defined) power and becoming more of a mentor and helper to younger people who are invested in the work and eager to lead.

Most of these relationships I’ve just described are not exactly like the particular bond that Brigid and Darlughdach shared, but I think that they echo the spirit of anamchara as Murphy describes it. I see anamchara as a model for aging with intention and purpose, and I’ll be lighting a single candle for both saints on February 1.

Know someone who might dig this public post? Please share!

If you’d like to learn more about St. Brigid, I have a lot to say about her in A Postmodern Witch’s Guide to Imbolc (available in both print and digital editions.) I also write about her connection to the goddess of the same name and share some ideas for celebrating the pagan holiday that coincides with the Feast of St. Brigid. While she didn’t make it into this year’s Imbolc zine, St. Darlughdach makes an appearance in the latest Postmodern Witch post, in which I introduce some other bits of Brigid trivia and share a ritual and a Tarot reading for Imbolc.

They also belonged to a religion that some queer theologians see as inherently queer because radical transformation and the dissolution of boundaries are essential elements of Christianity, but that’s a topic for another day. ↩

Comments ()