Archival Interview: Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea books are some of my favorite books ever, and they have been since I was a kid. I think it’s safe to say that I would not be who I am without those books. Way back in 2001, when The Other Wind came out, I had the pleasure of interviewing the author. We talked about some of the themes that run through all the Earthsea books.

Interview conducted in 2001

After reading The Other Wind, I reread A Wizard of Earthsea for the first time in a long time. I was struck by how much you seemed to know, right from the beginning, about Ged’s future and the whole history of Earthsea.

Ursula K. Le Guin: If I knew it all, I didn’t know I knew it. I was not thinking of that story as the beginning of a series. It was the first book for young adults I ever wrote, and the first heroic fantasy that I had written. I thought I would write it and go back to other things, yet I built into it an obvious lead-in to the next book… My unconscious mind is much smarter than I am sometimes.

Your style has changed over time. Your voice changes from the slightly distant style of myth to something much more familiar.

UKL: The first three books are written in that traditional, epic style, which is the way the great fantasies were being written at the time—or had been written. With Tehanu, I stopped writing from the point of view of the people in power and started writing from the point of view of the people who are not in power. I couldn’t keep up that high style. I needed to get a little quieter, a little plainer.

What made you decide to go back to Earthsea?

UKL: Well, the big, long gap was actually between The Farthest Shore and Tehanu… I always knew there needed to be a fourth book, but I couldn’t write it until… I guess I had to grow up. I had called Tehanu “The Last Book of Earthsea,” because I really thought that was where the story ended. That came out in 89, but after a couple of years in the 90s, I realized things were going on in Earthsea, that I had to catch up with it. I began asking some questions about why things were the way they were. I was thinking about its history, and that led me to the various stories. And then, when the stories were done, I went straight to The Other Wind, because there was the rest of Ged and Tenar’s story to be told, all this stuff about who the dragons are…

One thing that struck me while reading The Other Wind—and as I re-read the other Earthsea books—was the way you talk about good and evil, which are not popular concepts outside of fantasy. Do you have any idea why fantasy is such a popular medium for discussing good and evil?

UKL: Well, I do think a lot of novels handle good and evil, but, of course, the more realistic they are, the more embedded those concepts are. In fantasy, they can come out clearer, because things are more transparent in fantasy. The world is an invented world, and therefore, it is not as thick and dense and confusingly rich as the real world.

I think a lot of people think that fantasy oversimplifies the battle between good and evil… These guys have white hats, and these guys have black hats, but they are equally violent, and neither of them is really better than the other, and that is just a cop-out to me.

My master here, of course, is Tolkien. His bad people are pretty bad, all right, but you understand how they got that way. And his good people have a lot of trouble staying good. They’re really human, and that’s much more interesting.

In my books, there really aren’t any villains. There are difficult choices and there are moral dilemmas. I’m not particularly interested in violence, which I guess is why evil, to me, is a failure to do something you ought to do, rather than a malicious act. Not doing what you know you ought to do… Evil comes into you and you go along. Big battles with good people and bad people—that oversimplifies life immensely.

I don’t write about good and evil so much as I write about balance, about the idea that acts have repercussions. As one of the old wizards explains, the more power you have, the less you can do. You can’t do just what you want, but only what you must.

Tolkien’s name often comes up when your books are discussed. I’ve read that he didn’t see himself as a writer of fantasy so much as someone who was writing a history of a real place that had been lost…

UKL: Earthsea—as far as I’m concerned, it’s there. I can’t make what happens there. I have to find it out. I have to wait for it to happen, and then I can tell it.

IMAGE CREDITS:

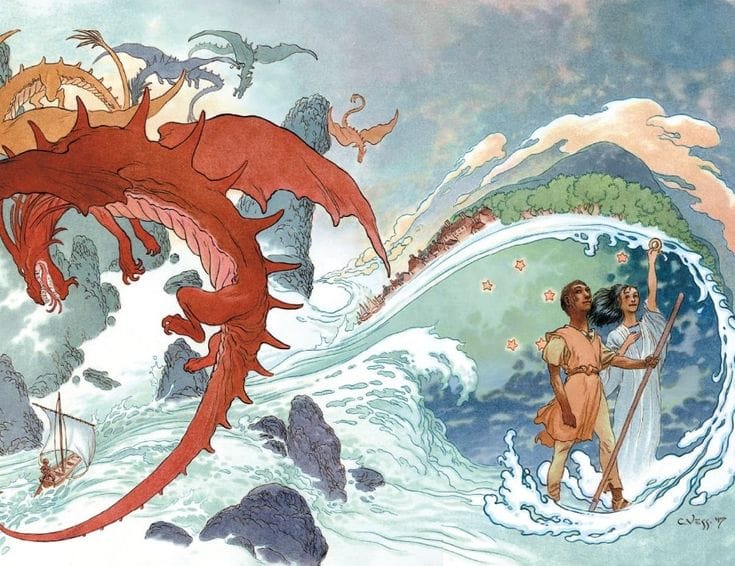

Artwork for The Books of Earthsea: The Complete Illustrated Edition by Charles Vess (2018).

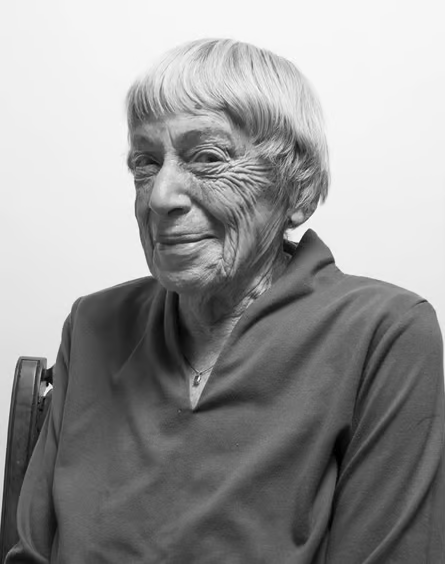

Photo of Ursula K. Le Guin by William Anthony for The Nation (2016).

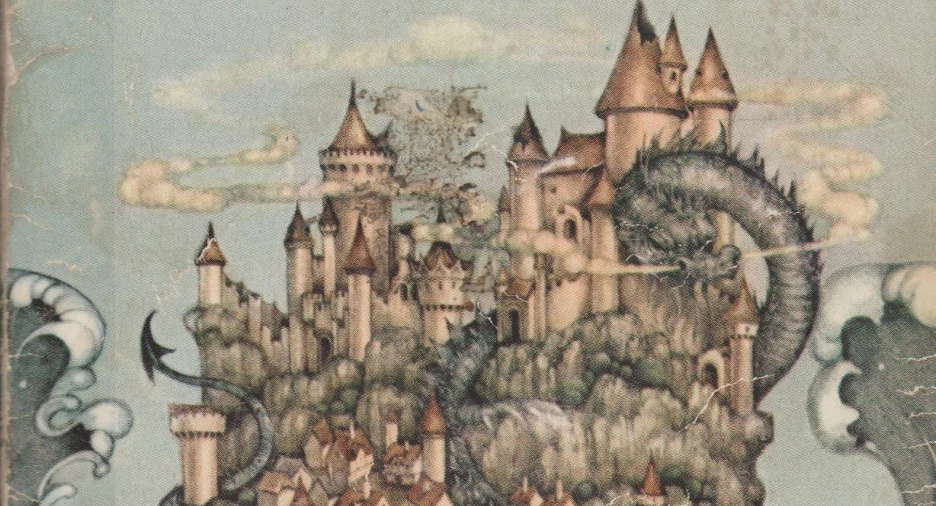

Detail of cover art for A Wizard of Earthsea by Pauline Ellison for Bantam Books (1975). This is the artwork on my dad's copy of the book, and I can say for sure that it shaped the landscape of my psyche. You can find the whole image and many more absolutely fantastic 70s cover art here.

Interior illustrations for A Wizard of Earthsea by Ruth Robbins for Parnassus (1968). I am so grateful that the Bantam paperback included these magnificent woodcuts. Robbins’ cover for the first edition of the book is one of the few to depict Ged as non-white, even though Le Guin is very clear that the skin of the Archipelagans varies from copper-brown to deep black.

Comments ()