13 Days of Sheela Na Gig: Pussy Power

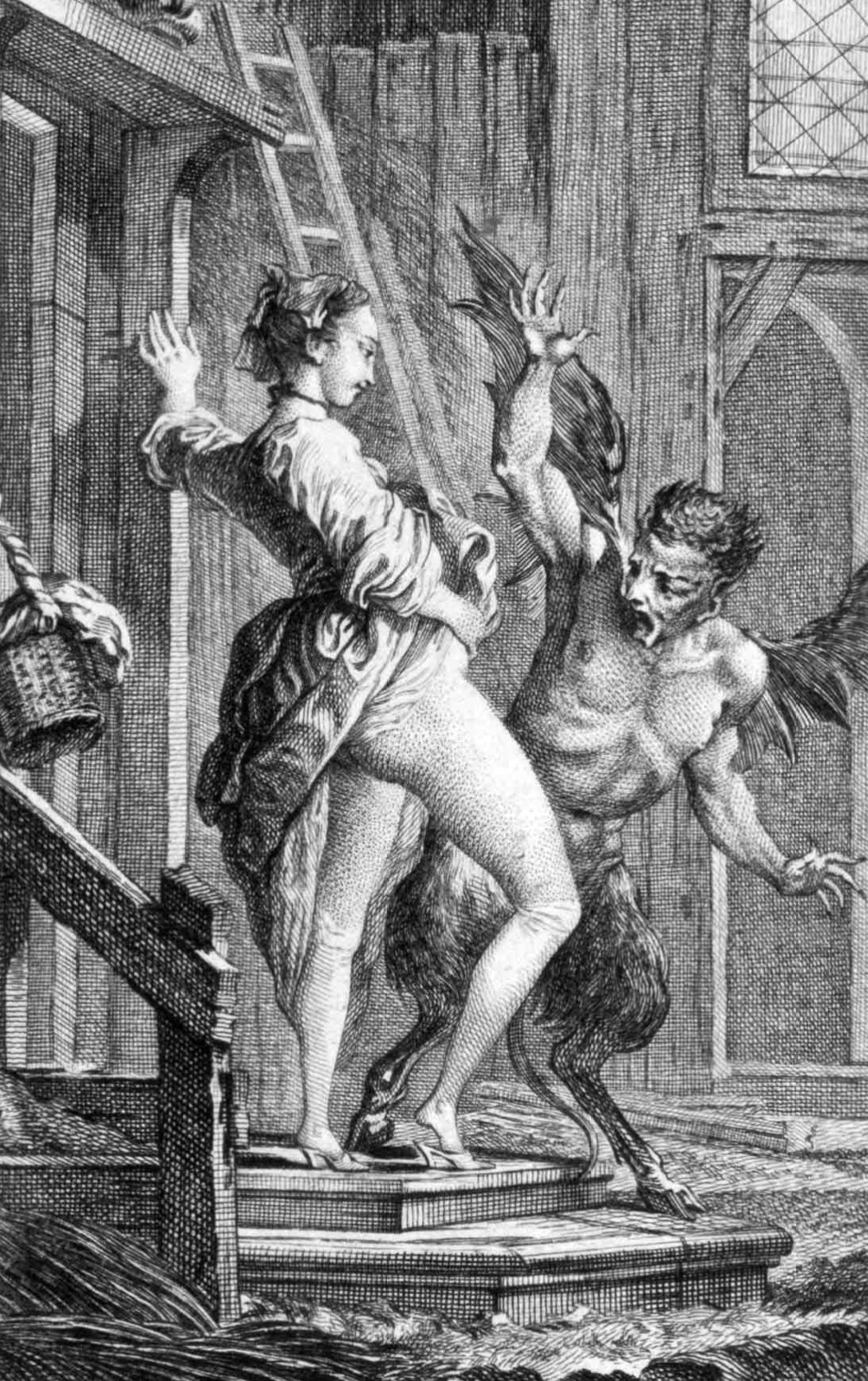

In Tales and Novels in Verse (1664), Jean de la Fontaine shares a poem called “The Devil of Pope-Fig Island.” In this story, a farmer successfully hoodwinks a demon—and instantly regrets it, as the demon is not at all happy about this turn of events. Luckily, the farmer’s wife, Perretta, can keep cool in a crisis. While the farmer hides in a vat of holy water, Perretta warns her adversary that he should flee before her husband, a cruel and violent man, abuses the demon as he has abused his wife. Then she lifts her skirts. Fontaine puts it this way:

For God’s sake try, my lord, to get away:

Just now I heard the savage fellow say,

He’d with his claws your lordship tear and slash:

See, only see, my lord, he made this gash;

On which she showed:—what you will guess, no doubt,

And put the demon presently to rout…

I stumbled upon this tale as I was researching Sheela Na Gig. What links Perretta and our Sheela is the idea that the very sight of a vulva is enough to scare away the devil.

The idea that female genitalia is a wound or gross imperfection has a long history in the West. At least as early as Aristotle, the perfect human form was male, and women were sort of undercooked men. Women, the thinking went, are more fluid than men and more permeable. Women, the thinking went, are leaky and changeable. Every month, they lose the life-sustaining essence of blood and, when a man plants his seed in them, they become a vessel for the child he engenders. In this context, of course the vulva is a site of horror, and we get anasyrma, the Greek word for lifting a skirt to expose one’s genitals or buttocks in protest.

In the latest issue of Croning, I cite scholars who suggest that Sheela Na Gig was supposed to have apotropaic power—that she’s been carved on churches and castles and bridges and elsewhere to ward off evil. A splayed vulva is, perhaps, the one characteristic that defines a Sheela Na Gig. Fontaine presents the vulva as supernaturally horrifying, but what if the vulva has apotropaic power because the vulva is the threshold between not being and being? What if the vulva provokes awe and terror because only those who possess vulva have the power to bring new life into the world? Maybe the vulva is only horrifying to those who would prefer to not think about the singular power the vulva represents? In her essay for the Spring issue of Croning, midwife Mel Bailey points out that reproductive freedom includes the power to end life, which we know is terrifying to the people who would take reproductive freedom away. The vulva made shockingly visible is, paradoxically, a sign of the inner workings of a pregnant person’s body—processes over which patriarchy can only ever have limited control.

There is cross-cultural scholarship about the use of anasyrma to avert the evil eye, to cast a curse and to fend off violence. I have a kneejerk reaction to universalizing and can only claim anything like expertise in a rather narrow set of topics, but I feel fairly comfortable sharing and talking about an example of anasyrma from Machiavelli, an episode from the life of Caterina Sforza that scholars, evidently, refer to as “the skirt-lifting incident.”

It goes like this: While her home is besieged after the death of her husband, the Contessa tells her enemies that she can encourage her people to surrender if only she’s allowed inside the castle, and she offers her children as hostages. Once she’s back inside the castle, she jeered at her former captors, telling them that she didn’t care about her children because she could make more while pointing at her “sexual parts.” Those who conspired against Caterina Sforza did not fare well. Whether or not this story is true is a matter of speculation, but I love the way it’s framed in this blog post:

In an article called “Sexuality, the Sheela na gigs, and the Goddess in Ancient Ireland,” Miriam Robbins Dexter and Starr Goode link anasyrma to Sheela Na Gig.

To the ancient Irish, there was great power in the nakedness of the female body. According to the tales of Cú Chulainn’s childhood deeds, the hero once went into a warrior rage. To diffuse his martial temper, his uncle, King Conchobor, devised a plan to tame him:

to send a company of women out toward the boy, that is, three times fifty women, that is, ten women and seven times twenty, utterly naked, all at the same time, and the leader of the women before them, Scandlach, to expose their nakedness and their boldness to him.

The whole company of women came out, and they all exposed their nakedness and their boldness to him. The boy lowered his gaze away from them and laid his face against the chariot, so that he might not see the nakedness nor the boldness of the women.

It’s instructive to note that the translation of the Táin Bó Cúalnge—The Cattle Raid of Cooley—that Miriam Robbins Dexter and Starr Goode use above seems to be idiosyncratic. I do not read Gaelic, but I do note that, where Dexter and Goode say “boldness,” many translations say “shame”—and this is true of the translation by Cecile O’Rahilly they cite in their sources. And it’s not clear from the formatting that large sections of this passage from the Táin Bó Cúalnge have been excised—including those that focus quite explicitly on the women showing their breasts, not their vulvas. From a scholarly standpoint, I feel like these authors are stretching a bit to make their point, while I also feel that the point they are trying to make resonates with current uses of Sheela Gig and contemporary expressions of anasyrma.2

I haven’t found a better contemporary image of anasmyra that this photo by Nicola Hunter.3 The moment I saw this photo, I started creating a myth in my head. It’s easy to imagine invaders repelled by this display. Maybe marauding armies would think twice about attacking a people so fierce that their women are bold enough to confront an enemy naked and jeering. Or maybe these women might have frightened men merely by showing their cunts. I don’t know. I am engaging in the venerable practice of making shit up. I can say for sure that when I tried to share this photo today, Facebook took it down and threatened to put me in Facebook jail. (They let me off with a warning and a ban from groups.)

Clearly, anasyrma still has the power to provoke, which should be surprising in an age where photos and videos of women not just spreading their legs, but also spreading their labia are never more than a couple of clicks away. What offends isn’t the nudity. It is, as Ian Chadwick says in his analysis of “the skirt-lifting incident,” women taking control—of their bodies, but also of the viewer’s attention. These ferocious, howling women are demanding that you see them. And they are doing nothing to make themselves attractive or seductive. They are managing the neat trick of being radically unfeminine while displaying the most categorically feminine parts of their bodies.

Having mentioned the man who is about to become the GOP candidate for president above, I would be remiss if I did not share how another image from Raising the Skirt went viral in 2018 and again in 2019.

Yes, conservatives on social media were claiming that this was a photo of women screaming at Donald Trump through their vaginas. To be clear, this strikes me as a perfectly reasonable thing to do and I might try it later myself. But no. This was part of a somatic workshop that was one aspect of Hunter’s piece, and it happened in 2014, back when the idea of Donald Trump as president of the United States was just a joke on The Simpsons.4

Looking for more vaginatastic content? Look no further than the Sheela Na Gig issue of Croning, now available in print and digital forms. With the print version you get a cool Sheela stencil and an extremely collectible trading card. With the digital version you get instant gratification. Either way, you get lots of vagina.

You’re thinking about pink pussy hats right now, aren’t you? I am, too. I started to write about them and realized that topic was really too complicated to get into here, but this iconic photo of Angela Peoples by Kevin Banatte and an op-ed by Ms. Peoples herself sum up a lot of this complexity. ↩

Dexter and Starr also include a few anecdotes that show up over and over again online but are difficult for me to substantiate, either because they rely on a single source with no supporting evidence or because I can’t even access that single source. The authors make reference to two influential books, The Witch on the Wall and Images of Lust, in their discussion of “living Sheela Nag Gigs”—women who could heal someone cursed by the evil eye by lifting their skirts. Dexter and Starr are careful to couch their suggestion that there has been a long tradition of such healers by framing the suggestion as a question but, still… They only support their suggestion with two bits of evidence that only seem to be connected by their suggestion.

They also mention a story of totally straightforward anasyrma from an article in the Irish Times on January 23, 1977:

“In a townland near where I lived [Caherfinsker, Athenry, County Galway], a deadly feud had continued for generations between the families of two small farmers. One day, before the first World War, when the men of one of the families, armed with pitchforks and heavy blackthorn sticks, attacked the home of the enemy, the woman of the house (bean-a’-tighe) came to the door of her cottage, and in full sight of all (including my father and myself, who happened to be passing by) lifted her skirt and underclothes high above her head, displaying her naked genitals. The enemies of her family fled in terror.”

If anyone reading this has easy access to the archives of the Irish Times, I would love to see this story in context. Sidenote: Unless there were several Walter Mahon-Smiths kicking around Galway in the parts of the 20th century, this Walter Mahon-Smith—typically described simply “an elderly man”—was probably the Walter Mahon-Smith who wrote I Did Penal Servitude, a book that led to calls for prison reform in Ireland, and who played a role in the creation of Boys’ Town. Does it matter that Walter Mahon-Smith was not just “an elderly man” for our purposes? Maybe not, but it seems sloppy to me to present him simply as such. I could be totally wrong in connecting these dots, of course. Which is why I would love to see that Irish Times article, as I suspect it might prove me right or wrong. ↩And I also thought about this Reuters photo of “Naked Athena” at a BLM protest in Portland in 2020. Like the pussy hats, this has layers—too many for me to parse here. But it is definitely a contemporary act of anasyrma. ↩

Comments ()