13 Days of Baba Yaga: Tin Can Forest

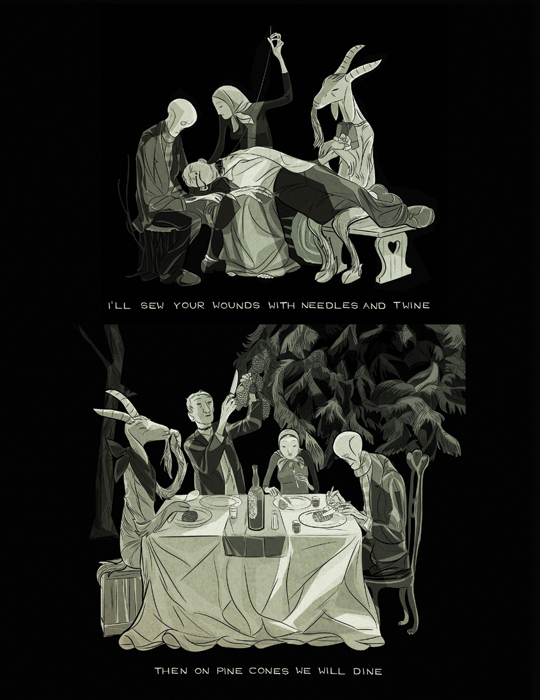

Whilst traversing the dense, darkened thickets of Tin Can Forest’s midnight woodlands, one may become disoriented by the bizarre, bestial, visions they encounter: shadowy, hircine cabals solemnly roaming about in ornate, traditional dress; nocturnal gatherings wherein witches, demons, and villagers skulk and cavort with all manner of talking beasts; families taking tea with raccoons and suffering the philosophical ramblings of an oddly articulate house cat.

The vivid imagery of these tangled tales and illustrated texts tugs at the memory, recalling vague, dreamy bedtime stories read to a younger you, still too green to understand the metaphors and allegories, yet on the verge of glimmering a deeper truth– for these darker narratives trigger memories more ancestral and arcane, reviving fears and beliefs borne in the blood, not learned during a child’s storytime.—S. Elisabeth, “Ritual and Reverie: The Occultastic Art Of Tin Can Forest”

This is what S. Elisabeth of Unquiet Things has to say about the work of Tin Can Forest, and I’m quoting because I really can’t improve on this. Tin Can Forest is Pat Shewchuk and Marek Colek, two Toronto-based artists who, in their own words, are inspired by “the forests of Canada, Slavic art, and occult folklore.”

I believe I got my first glimpse into their twilight universe when they collaborated with Pam Grossman on What Is a Witch, a mysteriously inviting introduction to the magical arts. Tin Can Forest has always put me in mind of Hellboy creator Mike Mignola, and as I’ve been revisiting the work of Ivan Bilibin, I feel like I see him, too. There are visual similarities, but also similarities in spirit. (As it happens, all three have taken Baba Yaga as a muse.) Tin Can Forest’s use of what looks, to me, like folk symbols also reminds me of pysanki and traditional Slavic embroidery.

Their Baba Yaga and the Wolf is rooted in folklore and in the landscape of Northern forests, and some of the elements that seem particularly contemporary may be older than we think. As I mentioned in my post about Nathalie Parain, children’s book illustrators were experimenting with modern art styles by the 20th century and, if I may be forgiven another comparison, I thought of Clement Hurd, the illustrator of Good Night Moon, the first time I looked at Tin Can Forest’s Baba Yaga’s Garden. Beyond that, Baba Yaga and the Wolf gets at an understanding of how folktales actually work. Baba Yaga may sometimes play—or seem to play—the role of an enforcer of cultural norms, but she is much more than that and folktales often take place in a world in which the difference between good and evil is complicated… and maybe either unsettling or exciting depending on where you’re coming from. Tin Can Forest gets this, and they make it visible.

Croning believes in supporting creators. Your free subscription keeps us going. Your paid subscription helps us pay contributors.

The preceding images are from Baba Yaga and the Wolf by Tin Can Forest. Their prints “Holy Vasilisa” and “Baba Yaga with Moth and Beetle” are also very weird and beautiful.

Comments ()