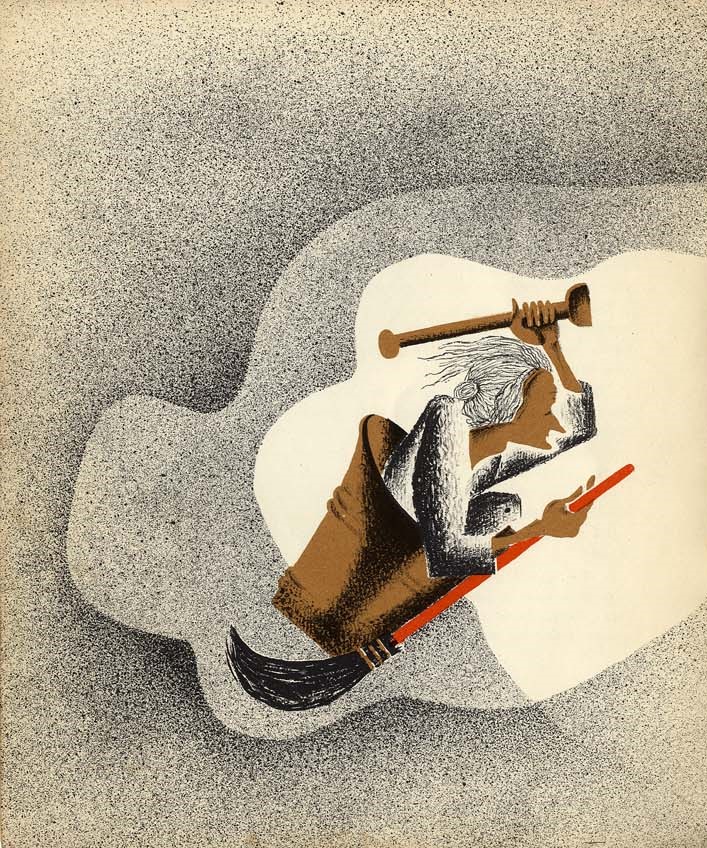

13 Days of Baba Yaga: Nathalie Parain

In 1925, Galina and Olga Chichagova illustrated a two-panel poster that called for a revolution in children’s illustration in the new Soviet Union. The left panel featured traditional characters from Russian fairytales and folklore – kings, queens, the Firebird, the witch Baba Yaga and, my favourite, a crocodile in elegant nightcap and dressing gown. “Out,” read the caption, “with mysticism and fantasy of children’s books!!”

Meanwhile, the right panel depicted what the sisters thought fellow artists should be illustrating to improve the first generation of little Soviet citizens. Under the beneficent eye of Lenin were images of young pioneers in red neckerchiefs, working on collective farms, as well as illustrations of Red Army cavalry troops riding into battle, factories, and aircraft. Anthropomorphised crocodiles, apparently, weren’t sufficiently revolutionary.

“Give a new child’s book,” went the caption. “Work, battle, technology, nature – the new reality of childhood.”—Stuart Jeffries, “Out with the bourgeois crocodiles! How the Soviets rewrote children’s books”

As the journalist Stuart Jeffries notes in his review of an exhibition of art from Soviet picture books, Baba Yaga is singled out as one of the fantastic figures no longer welcome is a post-revolutionary Russia. He goes one to describe an era in illustration that is often oppressive in content but visually exciting in its embrace of modernism. It wouldn’t be long, though, before all this avant garde experimentation would be replaced by state-mandated socialist realism. Many artists would eventually leave, with several of them landing in Paris. One of these artists was Nathalie Parain.

Parain was born Natalia Tchelpanova in 1897. She and her husband—philosopher and cultural attaché a the Frend embassy in Moscow—left the USSR for France in 1928. Parain’s boldly modernistic Baba Yaga was published in French, but there was also a Russian edition available during the brief window of time in which such books were still admissible. She is still considered a major figure in children’s literature.

These images are in the public domain.

Your subscription supports our work. Your paid subscription makes it possible to pay contributors. Please consider subscribing.

Comments ()