13 Days of Baba Yaga: For Superfans Only

My piece on Baba Yaga in the first issue of Croning is the distillation of a few years of studying and thinking about this figure. I stick to the written record as best I can and try to support my own ideas with evidence of scholars who have expertise that I absolutely do not have.

As I was putting this zine together, I also tried to focus on what Baba Yaga might mean for women who are aging. I hope that I put together an essay that’s useful.

In the course of reading up on Baba Yaga, though, I’ve stumbled across a few tantalizing bits that I haven’t been able to research but seem worth sharing for true nerds—with the understanding that this is nothing more than notes for further exploration. Here goes!

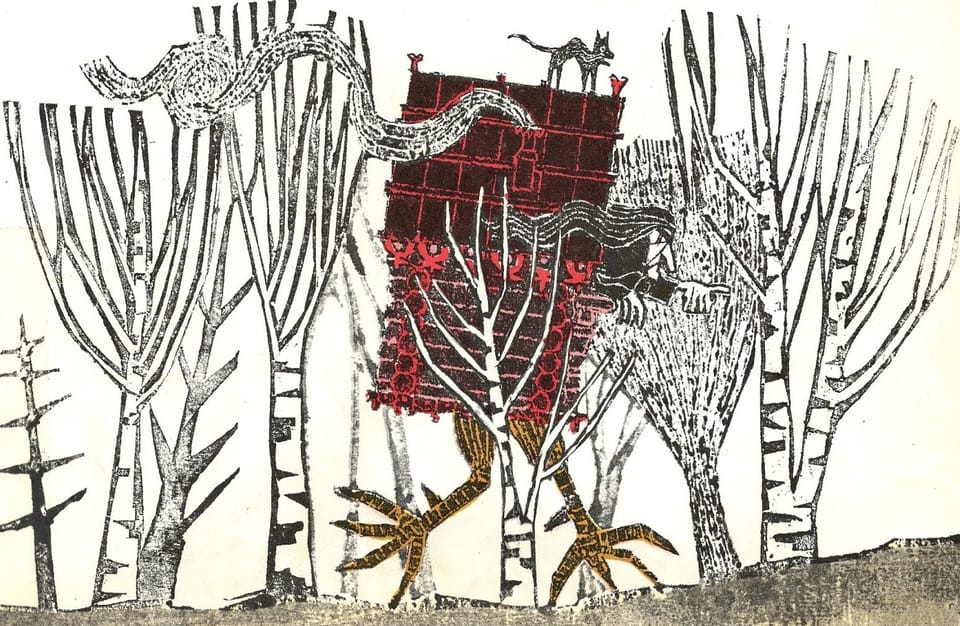

While trying to find images of Baba Yaga that I hadn’t seen before, I stumbled into a whole universe of Russian websites. The upside is that I found material I hadn’t encountered before. The downside is that I don’t read Russian and that trying to dig deeper with English sources was more than I was ready to do for this project. For example, I stumbled across a post that seems to be a lesson plan or curriculum for using stories about Baba Yaga in the classroom. Here are a couple of opening paragraphs:

The historian and writer A. Ivanov refers to the custom of the Urgo-Finns, which goes back to the times of paganism. They believed that the dead helped them from the other world, and after the death of a loved one, they made a babu, or ittarma, doll, into which the spirit of the deceased entered. Then they would wrap this doll in a fur coat made of animal skins, with the fur outside—a yaga. Such a fur coat was worn by women. Hence the name—Baba Yaga. There was matriarchy at that time, which explains the female gender of the doll.

After the “woman” was wrapped in a yaga, they made a sacred building, a somyah—a blockhouse “without windows, without doors” and placed [the] doll there. Together with the doll, they put jewelry and other attributes of the deceased and carried them into the thicket of the forest, far from the settlements. Then the building was erected on the trunks of felled trees so that neither animals could reach it nor people could steal it.

Cool stuff, right? Some of this material seemed to fit with analysis I’d already read. For example, some stories say that Baba Yaga’s grotesque body fills her whole hut, and Sibelan Forrester notes that this makes her seem like a corpse in a coffin. The idea of a community of mourners moving a doorless, windowless “house” far away from civilized land is a bit easier to imagine when we think of a coffin, rather than a domicile. And the idea that Baba Yaga exists in the wilderness between life and death is a concept that, I think, few scholars would argue against. As for some of the other details… The notion that Baba Yaga herself started out as a doll is neat, given the role a doll—a motanka?—plays in the stories of Baba Yaga and Vasilisa. But I have a lot of reservations about claims for matriarchal cultures that existed in the past, and you try tracking down a particular someone named Ivanov when you don’t know Russian and only have a first initial for a given name. So, for now, these are just some interesting ideas about a wildly polyvalent figure—or at least they are for me.

The photo above is a recreation of a traditional Sámi storage hut at an open-air museum in Sweden. The Sámi are often described as Europe’s last living indigenous people, and their traditional homeland encompasses parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. You can see why I’m sharing this photo here, right?

I tend to get a bit fussy about overly simplistic “rational” explanations for phenomena we encounter in myth and folklore, but this seems… relevant. I haven’t come across anything that suggests that Baba Yaga is a Sámi figure. Does that mean that Baba Yaga’s hut looks like a Sámi storehouse because, like the Sámi, Baba Yaga is an outsider? Or does it mean that, somewhere in the distant past, was inspired by the sight of a Sámi storehouse and created a house that walked on chicken legs? Or am I just talking shit?

Scholars who know more than I do have some ideas. In an essay, Helen Pilinovsky cites Soviet folklorist Vladimir Propp to suggest that Baba Yaga’s home “might be related to the zoomorphic izbushkii, or initiation huts, where neophytes were symbolically ‘consumed’ by the monster, only to emerge later as adults.” Based on what I know, I feel pretty good about having used some of what is said here in my own essay. But, once again, my lack of Russian is a roadblock.

If I google “izbushkii,” a couple of things happen. One is that I learn that an izbushka is wooden cottage that might be used for storage or might be a home for peasants. If it was a home, it was likely dominated by a stove (which matters when we’re talking about Baba Yaga.) I also find a lot of modern structures—novelties, neither houses nor storage sheds—clearly designed to look like Baba Yaga’s hut on chicken legs. Your results may vary, but my experience points to one of the complexities of working with folklore.

Folklore isn’t a pure product of the naïve id that flows upward from the unlettered into mass media and from there into “literature.” Folk culture, mass culture, and “high” culture are constantly intermingling. So, yeah, image searches for izbushkii are going to start turning up iterations of Baba Yaga’s house for English speakers as this Russian word becomes more associated, click-by-click, with Baba Yaga.

I also have some things to say about Baba Yaga as phallic mother, but I think I’m done for the night.

Comments ()